First, let’s have an experiment.

Picture a dangerous woman.

How old is she? What does she look like? What kind of danger does she present?

Remember that image. We’ll get back to that later.

Snow White is dumb

A while ago, my 3 year old daughter asked me for a bedtime story. I was too tired to think of anything novel, so I went with the classic fairy tale Snow White.

As I watched my daughter falling asleep, I thought: “What a dumb, dumb story!” - the protagonist is passive and submissive, has no agency and falls victim to subsequent plots of the evil queen, and the happy ending of the most popular Disney’s version - a kiss from a prince miraculously curing a deadly poisoned princess - is just pure idiocy.

As it turned out, later that night I read Rob Henderson’s post about the Male Warrior Hypothesis, which is defined as follows:

Within a same-sex human peer group, conflict between individuals is equally prevalent for both sexes, with overt physical conflict more common among males

Males are more likely to reduce conflict within their group if they find themselves competing against an outgroup.

Rob describes of several types of indirect aggression typical in female intrasexual competition: rumor spreading, gossiping, ostracism, and friendship termination. At the extreme, it can take a form of vicious backstabbing. Rob includes an example, the story of Helena Valero, who spend decades living with the Amazonian tribes:

Upon arriving in a new tribe, Helena was given a packet of poisoned food by one of the women, who told her to eat it or give it away. The woman knew that Helena will either eat it and die, or, if she gives it to someone else who eats it and dies, will be blamed and either killed or banished from the tribe.

This is basically an improved plot of Snow White.

I also thought about Robert Bly’s Iron John: A Book About Men, an elaborate exegesis of a lesser known Brothers’ Grimm fairy tale of the same name. Bly believed that classic fairy tales are vessels of ancient folk wisdom. His thorough analysis of all themes and motifs of the tale unveils the proper, natural way of boy’s maturing into adulthood, in many ways different from how boys become men in modern world - one of the causes of the modern manhood crisis.

Then I realized: “Maybe the Snow White tale isn’t that dumb after all? Maybe I got it all wrong? And maybe it’s just not a tale for me?“

The Princess with a Thousand Faces

The tale of Iron John is a prime example of the monomyth, also known as the Hero’s Journey - a common template of epic stories described by Joseph Campbell in his book The Hero with a Thousand Faces:

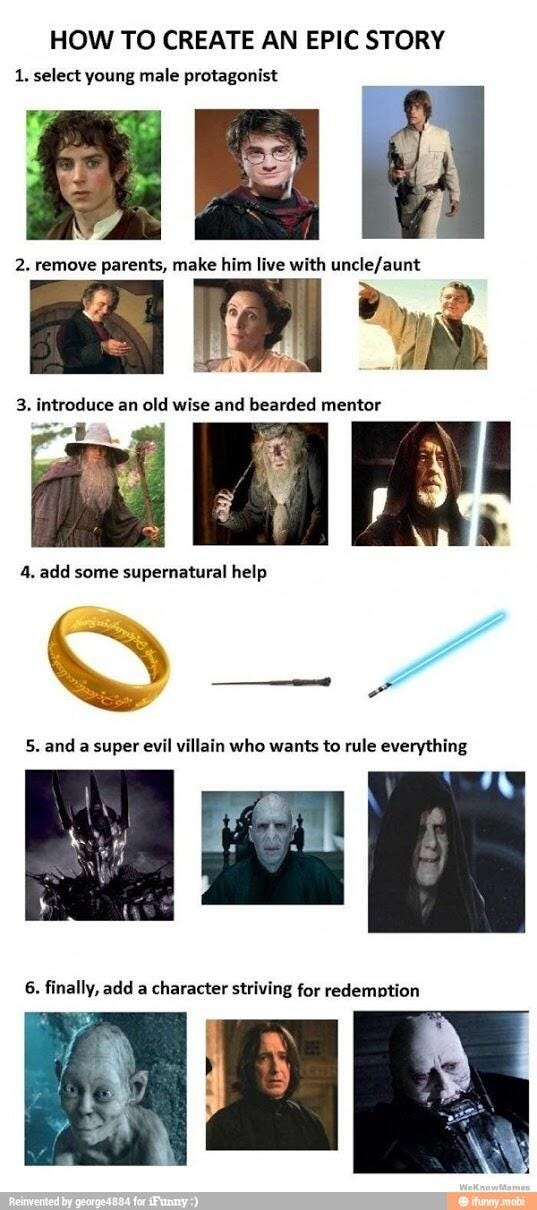

The Hero’s Journey pattern can be seen in stories forming the backbone of our culture since the dawn of ages: from ancient myths, the Bible, medieval legends, romantic novels to modern mainstream culture. It is why fantasy nerds sooner or later realize that The Lord of the Rings, Harry Potter and Star Wars all tell same story:

The Hero’s Journey monomyth is deeply rooted in our collective conscience - people who see their life story as a Hero’s Journey consider their lives more meaningful.

The Snow White tale doesn’t match the Hero’s Journey template. However, we can draft an alternate monomyth template, that forms the baseline of many similar fairy tales with female protagonists. Let’s call it The Princess’ Journey:

A conflict ensues between the Princess and the Evil Woman. The Evil Woman unleashes a covert plot of indirect aggression to hurt the Princess and move her out of the picture. The Princess is passive and oblivious, and she falls victim to the Evil Woman’s woes, until her situation becomes critical. Eventually, the Princess is saved by an unexpected divine, magical or third party intervention - Deus Ex Machina.

The Princess is a young girl that becomes a rival or a threat for the Evil Woman - an older, incumbent, powerful, high status woman; typically a stepmother, evil queen or witch (Snow White is notable for a 3-in-1 combo).

David Robinson did a sentiment analysis of over 100,000 stories. His conclusion is that the average story we tell ourselves can be summarized as: “Things get worse and worse until at the last minute they get better“:

Both monomyths - the Hero’s Journey and the Princess’ Journey - follow this most basic pattern.

Women against women

Evolutionary psychology is the science of human nature - it provides a part of the explanation of why we do what we do. The other part is nurture - conformance to social norms. When deciding on what to do or how to behave, we sometimes need to resolve the conflict between nature - what helped our ancestors survive and reproduce in the past - and nurture - what other people expect from us now. In a way, nurture is also part of nature - evolution conditioned us to follow social norms, as it benefited our ancestors.

Many evolutionary psychology insights are based on the notion that most humans lived in small hunter-gatherer communities for hundreds of thousands of years. Then, society started to evolve quicker than our brains. 10 years of social media, 100 years of other modern technology, 1,000 years of urban life, and even 10,000 years of agriculture is just too little time for our brains to fully rewire and adjust to the new circumstances. Studies of currently existing hunter gather communities can therefore yield surprisingly relevant insights about our human nature.

Both men and women compete for mates in their youth. However, in patriarchal societies, women must compete their entire life to secure continuous support and resources for them and their children from men. Obviously, thanks to 100 years of emancipation and gender equality efforts this is no longer the case in most developed countries, but as noted above, 100 years is not nearly enough for the brains to adjust.

Female intrasexual competition is a common theme in Rob Henderson’s Substack posts and the works of evolutionary psychologists such as Tania Reynolds. Learning about it is fascinating for me since, as a man, I naturally don’t experience it, and before reading about it, it didn’t seem very real to me - I thought that the Mean Girls type teenage drama or Devil Wears Prada type corporate stories are just Hollywood tropes and things that don’t actually happen in real life apart from the far fringes of the society, much like extreme male violence in action movies.

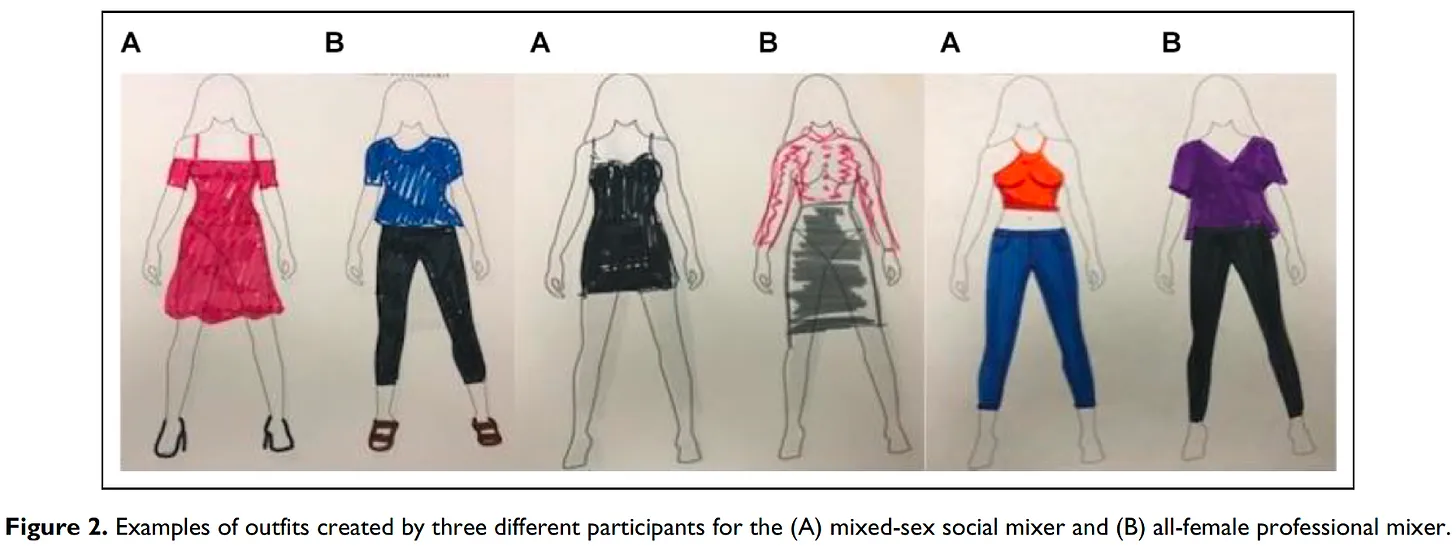

Current research confirms that scantly clad or heavy makeup wearing women are prone to higher risk of aggression from other women.

Rob also notes how attractive female students of elite universities often dress modestly, to optimize the benefits of attractiveness versus the cost of increased risk of being victimized by their peers.

The Princess Journey is actually a cautionary tale warning young women against the risk of conflict with the Evil Woman, who has an upper hand - high status, cultural/social/financial capital, life experience and secret knowledge (→ the witch). The Princess is always the disadvantaged side. The Deus Ex Machina ending is clearly far-fetched, so the obvious conclusion should be that in a real life scenario, the Princess’ passive and oblivious attitude would quickly lead to her demise.

The Forbidden Tale

Today, the above interpretation is not obvious. For Snow White, most of the interpretations I found are consistent with the one I got from ChatGPT:

These popular interpretations can be summarized as “Don’t be like the Evil Woman”, which is easily extrapolated to “Be like the Princess”.

This reasoning is false, and is driven by two biases - the contrast between the (clearly) Evil Woman and the (presumably good) Princess and the Virtuous Victim effect, a tendency to consider victims of unfair transgressions as more moral than non-victims. Snow White and other Princesses typically have no agency and passively follow the course of events as they unfold. Unlike the Hero, they are usually not forced to make hard choices between right and wrong, which could provide a testament to their perceived high moral character.

Moreover, the “Don’t be like the Evil Woman” interpretation is not evident in many Princess’ Journey tales. In the original versions of Cinderella, Sleeping Beauty, Little Mermaid and Snow Queen, the Evil Woman faces no punishment for her dirty deeds against the Princess - she just keeps calm and carries on. A cynic could even conclude that the Princess Journey tales are actually instruction manuals for Evil Women on how to get rid of a threatening Princess.

I believe that the correct interpretation is: “Don’t be like the Princess” - passive approach will make you fall victim to the Evil Woman, and Deus Ex Machina will not come to the rescue in real life.

Stories written by the victors

Why the doesn’t the above interpretation seem as obvious as the one from ChatGPT?

Fairy tales are memes that evolve over time, from folklore, through 19th century fairy tale collections, to Netflix shows. To make things simple, let’s use the terms below:

The original - Fairy tale from the classic collections of Brothers Grimm, Hans Christian Andersen and Charles Perrault.

Classic adaptation - 20th century full length animated feature, typically produced by Disney.

Contemporary adaptation - 21st century feature, CGI or live-action with lots of VFX.

Recent changes in Princess’ Journey tale storylines that bring them closer to the more established Hero’s Journey template can be classified into three types revisionist strategies.

Some classic adaptations are examples of heroic revisionism 1.0: replacing the typical Princess’ Journey climax with a heroic clash between the Evil Woman and a secondary character, the Prince. This fight can only be morally viable if the Evil Woman is dehumanized - turned into an inhuman monster, a demon which can be bravely fought and slain by the Prince, as the Princess passively observes.

Heroic revisionism 1.0 was typically used to simplify the storyline - some original fairy tale endings could seem utterly confusing for the modern audience.

For example, the original plot of Little Mermaid by Andersen is largely unknown, most of us are more familiar with the 1989 Disney’s adaptation.

The original story includes a complex theological theme: The Mermaid wants to become human upon learning that humans have an immortal soul, while mermaids turn to sea foam at death and cease to exist. The Prince does not fancy the Mermaid, instead, he genuinely falls in love and marries another girl. The mermaid is given an option to save herself if she kills the Prince, but eventually she is unable to hurt her loved one and dies. However, she does not perish, but miraculously (Deus Ex Machina) turns into a benevolent spirit and gets a chance for redemption and, eventually, an immortal soul - a happy ending, according to Andersen.

No wonder why Disney screenwriters replaced the ending with a sea battle with the evil witch turned into a giant sea monster, defeated by the Prince impaling her with his ship's bowsprit. Similarly, the hundred-years sleep of the Sleeping Beauty was replaced by the clash between the Prince and evil witch Maleficient in Disney’s classic adaptation.

In more contemporary adaptations, revisionism was required for political correctness, which led to inventing new types of revisionism.

The first one is heroic revisionism 2.0: the Princess directly confronts and defeats the Evil Woman. Examples include modern adaptations of Snow White: 2012 movie Snow White and the Huntsman and the new version from Disney, planned to be released next year, whose creators already revealed, that Snow White will become “a fantastic leader” that “is not gonna be saved by the Prince”.

The newest version of Little Mermaid, known example of race revisionism, also includes a 2.0 upgrade of the heroic revisionism - this time, the Mermaid is at the helm of the ship which rams and kills the evil sea witch.

In Alice in Wonderland, a more contemporary original tale, the Princess’ Journey theme appears in the end, as the conflict between Alice and the evil Queen of Hearts rapidly escalates: when the Queen finally commands “Off with her head!”, Alice is saved by Deus Ex Machina - she wakes up from her dream. However, in Tim Burton's contemporary adaptation, Alice ends up in a shiny armor and a sword in her hand, fighting the evil Queen, her army and her pet Jabberwocky.

Finally, lets discuss the state-of-the-art revisionist invention: antiheroic revisionism. This method flips the Princess’ Journey narrative on its head by making the Evil Woman the actual protagonist. An origin story is created to explain how the Evil Woman was hurt in the past, and how the bad things she does are either crimes of passion or a just retribution. The Evil Woman becomes a tragic antihero, her crimes are “the approach to the inmost cave” and a step towards redemption - her story is now basically a Hero’s Journey.

20 years ago, researchers discovered the WAW - Women Are Wonderful - effect: a cognitive bias that makes people associate more positive attributes with women when compared to men. Today, feminism dominates the mainstream popular culture, and an Evil Woman hurting another woman is just not politically correct. Hence, antiheroic revisionism, which allows retelling classic fairy tales in a politically correct way.

The only politically correct type of an evil woman is the femme fatale - a strong, independent, agentic and attractive woman who triumphs over a stupid, careless, sex-driven male.

Now, it’s time for the second part of our experiment: Who did you imagine as a “Dangerous woman” when you started reading this essay? Try to recall your impression from the beginning, not who you thought of now. Please vote:

If my gut feeling is correct, most of you probably thought about the femme fatale. If so, this will be a testament of the effectiveness of the deconstruction of the Evil Woman archetype. Otherwise, my assumption can at least be confirmed by the most upvoted answer to a question about the “Dangerous Woman” on Quora:

Disney’s 2014 movie Maleficient is a prime example of antiheroic revisionism. 2021 movie Cruella is arguably also one - 101 Dalmatians is not a Princess’ Journey tale per see, having a pack of puppies instead of the Princess, however Cruella is definitely a classic Evil Woman. Thus, Disney decided to make another movie to build a more favorable narrative around that character.

The most sophisticated use of antiheroic revisionism is Frozen. Walt Disney Studios had been developing an animated feature based on Andersen’s The Snow Queen on-and-off since the 1940’s, but numerous projects were shelved (presumably, after failing to draft a workable screenplay using heroic revisionism 1.0) and eventually, a classic animated adaptation was never released. However, in 2013 they managed to put it together with CGI, antiheroic revisionism and joining the original characters of Kai and the Snow Queen into one - the protagonist, Elsa: a conflicted, tragic antihero. As a teenager, Elsa is effectively both an adult Evil Woman - a witch & evil queen - and an innocent child, the victim. Her escape and self-exile in an ice castle on a mountain top is basically her kidnapping herself.

Beware of the Evil Woman

Why is any of this important?

We all need cautionary tales - they prepare us for unlikely events with dire consequences, by showing us how to recognize and avoid them or manage them as they happen.

The tales of monsters and other fantastic creatures have made children less likely to wander off into the woods and get lost. However, according to Robin Dunbar’s Social Brain Hypothesis, living in communities changed the game for humans: the wild beasts lurking in the woods were no longer the main threat - other humans became the most dangerous animals out there. And so, cautionary tales about conflicts amongst humans became the most important kind.

Gender-wise, there are four possible types of human conflict cautionary tales:

Man-hurts-man: the Hero’s Journey.

Woman-hurts-man: the Femme Fatale.

Man-hurts-woman: patriarchy & abusement - Little Red Riding Hood and other stories about the Big Bad Wolf.

Woman-hurts-woman: the Princess’ Journey.

With feminism looming, the first three types remain politically correct, but the fourth one does not. And that is a problem.

In the old times, the children were told fairy tales by their parents and other caregivers. Today, they are supported by books, toys, and spin-off media from franchises spearheaded by mainstream movie adaptations. Revisionist changes from movies propagate to all related media and merchandise, creating a pervasive cultural experience - a content machine catering to consumers of all ages, from toddlers to young adults.

So far, we can see that the above process of shoving the true meaning of the Princess Journey down the memory hole has been very effective - otherwise, you wouldn’t be reading this essay right now. While it does slightly improve the cultural perception of women, it also deprives them of a cautionary tale that would be helpful if one ever finds herself in the crosshairs of an Evil Woman in a Princess’ Journey scheme.

Hence, I believe that the whole operation backfired and is a net negative for women - it’s effectively antifeminist.

A few years ago, a close friend - let’s call her the Princess - told me about a problem she had at work: one day, the outcomes of her previous day’s work were damaged in a way that hinted at her negligence. Yet, she insisted that everything was done and secured correctly. The only other person who had access to the room was an older, incumbent Evil Woman with a history of indirect aggression against the Princess.

As a man, initially I didn’t think that the Evil Woman could have tampered with the items, I even tried to gaslight the Princess into believing that she might have messed something up herself after all.

Some time later, the Princess quit that job, with poor employee relations as one of the decisive factors. She has removed herself from the picture. The Evil Woman won.

Evil Women exist, but it’s not like they are holding out for a Princess to harm. I’m no moral philosopher, but from a behavioral standpoint, a lot of what we consider “evil” is poor self-control and/or psychopathy, which both make some of us less likely to suppress acting on impulses coming from the darker side of our human nature.

It is natural for humans to urge for aggression when threatened - but not socially acceptable to follow through.

The Princess’ Journey could be described in a behavioral way like this:

Woman B feels threatened by woman A. If woman B has low self-control/psychopathy, she might act with covert, indirect aggression against woman A. And if woman B is more powerful (higher status, resources, etc.), woman A is in danger and should proceed with caution.

A male version (a part of a Hero’s Journey) would look like this:

Man B feels threatened by man A. If man B has low self-control/psychopathy, he might act with open, direct aggression against man A. And if man B is more powerful (bigger, stronger, etc.), man A is in danger and should proceed with caution.

“Evil” doesn’t seem like the best description of man B and woman B - “dangerous” sounds more accurate though. As noted before, “dangerous woman” is more associated with the femme fatale, so for the sake of consistency, let’s stick with the Evil Woman for now.

In a way, “Evil Woman doesn’t exist” or “Be like the Princess” are Rob Henderson’s luxury beliefs - views that benefit the elite but harm the poor and middle class. The Princess Journey is a high/low status dynamic, and it’s best for the high status Evil Woman if the low status Princess remains passive and oblivious. Also, a true, high status Princess doesn’t need to see a movie or hear a story to learn how to deal with an Evil Woman - she is already on top of the elite status games and female intrasexual competition.

So, if you ever find yourself in a Princess’ Journey scenario, what do you do?

First, let’s rule out the ineffective strategies:

“Be like the Princess” (baseline/ChatGPT strategy) - this only works with the Deus Ex Machina cheat code.

“Holding out for a Hero” (heroic revisionism 1.0) - this only works with the Turn Evil Woman Into An Actual Monster cheat code.

As Richard Hanania pointed out, women’s tears win in the marketplace of ideas - it is hard for a man to effectively interfere in a female emotional conflict.“Be the Hero” (heroic revisionism 2.0) - one of the unintended consequences of feminism and gender equality that, arguably, also backfired against women, was imposing the male ethical norms stemming from The Male Monkey Dance and codes of honor on the entire population. This leaves most women defenseless - indirect aggression is now morally unacceptable, while open, direct aggression is something most women are naturally not comfortable with.

Trying to openly confront another woman in a male, heroic way might possibly work if both women are autistic and/or woke enough to assume a male mindset, but otherwise it might just make things worse or become a handicap. The codes of honor limit the male aggression against ingroup members to allow dominance without completely obliterating the opponent (he might later become an valuable ally in a fight against the outgroup). But with female aggression, there are no holds barred. In a clash of two equally capable opponents with different aggression styles, the one with female aggression style will always prevail.“She just needs help” (antiheroic revisionism) - considering the Evil Woman a poor, troubled soul and trying to help her instead of confronting her seems like a noble and politically correct way to go. While this makes a good Hollywood movie plot, it’s easier said than done in real life.

It’s hard to therapize your way out of the conflict if you are the low status counterpart in a high/low status setting, and finding a way to subvert or at least equalize the status dynamic might be even more challenging.

Now, what could actually work?

There is one classic fairy tale that is very much like the Princess’ Journey, but not quite so. It’s Hansel and Gretel.

The witch lures Gretel and her brother into her gingerbread house and traps them inside. Gretel is initially submissive, follows the witch’s orders and manages to win her trust. As the witch prepares to cook and eat the children, she asks Gretel to check the oven. Gretel pretends she doesn’t understand, so the witch leans over the oven herself to demonstrate. Then, Gretel quickly pushes her inside and slams the door shut.

Despite the physical push, this was not a male, heroic confrontation - Gretel used deception and distraction to get an upper hand and defeat her opponent. She outsmarted the witch, beating her at her own game.

By now, it should probably be obvious why Disney never attempted to make a mainstream Hansel and Gretel movie1.

If you can’t quit the game, change the rules, get saved by Hero or a divine intervention, the best thing you can do is understand the rules of the game and play your absolute best. The game might be rigged, but it doesn’t mean that you can’t win.

Don’t be like the Princess. Be like Gretel.

This is a translated & updated version of my essay originally published in Transhumanista newsletter in Polish in January 2024.

Fun fact: A low budget Hansel and Gretel TV special directed by Tim Burton was made and aired on Disney Channel in 1983… once - Disney’s thought police immediately realized their horrible mistake. The special disappeared from the face of the earth, only to reemerge years later at Burton art exhibitions and online.

I just came across your Substack. Very interesting post.

A character that is common in Princess Journey stories that you did not mention is the Fairy Godmother. Consistent with your argument here, I think the Fairy Godmother makes an important pedagogical point to girls that there are older women who will help with guidance and glamour (here, meaning both beauty and magic) to evade the designs of the Evil Woman and win the heart of the Prince.

Interesting thoughts! I agree that the Evil Woman has done a magnificent PR job on herself. If you’re interested in more analysis, Marie Louise Von Franz did a lot of work on fairytales focused on women’s journeys. Her work “the feminine in fairytales” is an excellent starting place.

Hers is a jungian interpretation so the role of the male at the end to save the princess may be less about finding an external savior but more of exactly what you describe - becoming less princess like and forming a union with her internal “male” energy which gives her the strength and the skill to overcome the evil witch.